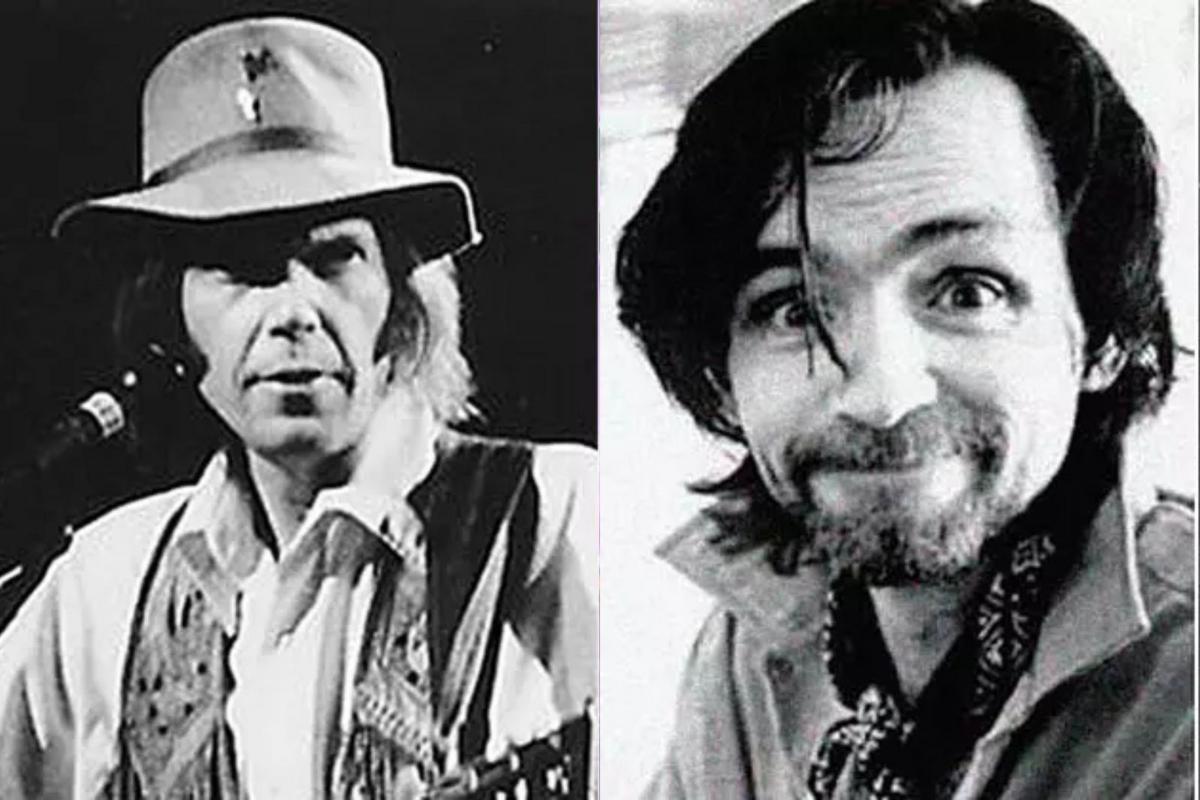

Before he was a convicted murderer, Charles Manson was an aspiring musician, who, at one point, rubbed shoulders with Neil Young.

That was thanks to Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys. Wilson and Manson had become friends in 1968, occasionally making music, hanging out with girls and experimenting with drugs, none of which would have raised too many eyebrows at that time, even if Manson appeared a bit more intense than other people around him.

“Sometimes Charlie Manson, who’s a friend of mine, says he’s god and the devil. He sings, plays and writes poetry,” Wilson told Rave magazine that year (via Far Out Magazine).

“Dennis was enthralled by him at one time,” his Beach Boys bandmate Mike Love recalled to ABC News in 2017, “and it didn’t hurt that Charlie Manson came with this group of girls – young girls, who were very enamored with Charlie, and looked up to him as a leader.”

As far as Wilson was concerned, Manson was simply an eccentric but well-liked burgeoning artist who had an interest in pursuing music more seriously. Manson expressed a desire to meet Mo Ostin of Reprise Records, and so Wilson introduced him to a fellow Los Angeles dweller, Young, who was signed to the label.

Like Wilson, Young also found Manson to be somewhat over-the-top and strange but creative nonetheless.

“He had this kind of music that no one was doing,” Young explained in a 1985 interview with writer Bill Flanagan. “He would sit down with the guitar and start playing and make up stuff, different every time, it just kept comin’ out, comin’ out, comin’ out. Then he would stop and you would never hear that one again. Musically I thought he was very unique. I thought he really had something crazy, something great. He was like a living poet. It was always coming out.”

Manson having “followers” at that point didn’t seem out of the ordinary to Young: “He had a lot of girls around at the time and I thought, ‘Well, this guy has a lot of girlfriends.'”

READ MORE: Neil Young Albums Ranked Worst to Best

In fact, Manson possessed a kind of improvisational skill that impressed Young.

“His songs were off-the-cuff things he made up as he went along,” Young wrote in his 2012 autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace, “and they were never the same twice in a row. Kind of like Dylan, but different because it was hard to glimpse a true message in them, but the songs were fascinating. He was quite good.”

Good enough that Young even said it to an executive at Reprise. “He’s just a little out of control,” he recalled in a documentary years later (via The New York Times). Manson even auditioned for producer Terry Melcher, who’d worked on the first two Byrds‘ albums. Melcher eventually declined to sign him and both he and Wilson moved on from the relationship.

Of course, nothing ever became of Manson’s music career. In 1971, he was convicted of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of seven people, including actress Sharon Tate who was killed in August of 1969, roughly six months after Manson had been introduced to Young.

“I don’t know why he did what he did. But I think he was very frustrated in not being able to get [a record deal], and he blamed somebody,” Young said in 1985. “And he really was unique. But I don’t know what happened. I don’t know what they got into. I remember there was a lot of energy whenever he was around. And he was different. You can tell he’s different. All you have to do is look at him. Once you’ve seen him, you can never forget him. I’ll tell you that. Something about him that’s…I can’t forget it. I don’t know what you would call it, but I wouldn’t want to call it anything in an interview. I would just like to forget about it.”

Not all that long after Manson’s conviction, Young did what any normal person would do: he wrote a song inspired by the events from the perspective of a bloodthirsty killer. That song was called “Revolution Blues” and it appeared on his 1974 album On the Beach: “Well, I hear that Laurel Canyon is full of famous stars / But I hate them worse than lepers and I’ll kill them in their cars.“

Listen to Neil Young’s ‘Revolution Blues’

‘Don’t Sing That’

This was evidently a step too far for Young’s Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young bandmates when the group went on tour that year.

“Man, they didn’t know if they wanted to stand on the same stage as me when I was doin’ it,” Young later told journalist Nick Kent. ‘I was goin’, ‘It’s just a fuckin’ song. What’s the big deal? It’s about culture. It’s about what’s really happening.'”

David Crosby himself had played rhythm guitar on the studio version of the song and the whole thing unnerved him — “Don’t sing about that. It’s not funny,” he reportedly told Young then, according to

You might think that a life sentence in prison would put an end to Manson’s musical dreams, but it didn’t. In 2009, it was reported that he’d sent a note to producer Phil Spector, then in prison himself for the second-degree murder of actress Lana Clarkson, hoping for a behind-bars meet-up.

“A guard brought Philip a note from Manson, who said he wanted him to come over to his [lockup]. He said he considers Philip the greatest producer who ever lived,” Spector’s wife Rachelle told the New York Post then (via Rolling Stone). “It was creepy. Philip didn’t respond.”

Listen to Neil Young Perform ‘Revolution Blues’ Live in 1974

Allison Rapp is a New York City-based music and culture journalist. Her work has appeared in Brooklyn Magazine, Insider, Rock Cellar, City Limits and more. She is also the host of Big Yellow Podcast, a show about Joni Mitchell. She tweets at @allisonrapp22.

Neil Young Archives Albums Ranked

Unreleased LPs, concert recordings, classic bootlegs and more from one of the deepest vaults in rock history.

Gallery Credit: Michael Gallucci