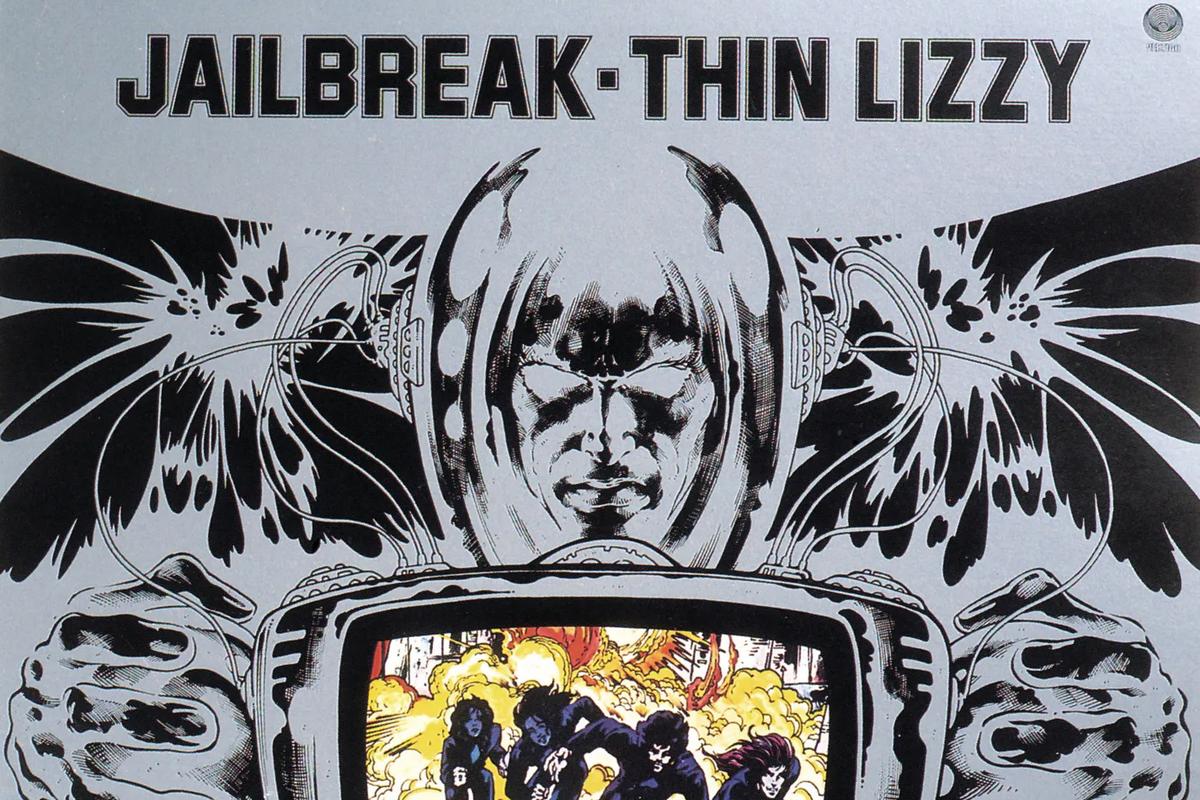

Thin Lizzy were on the verge of being dropped at the time they made the Jailbreak album, which was released in 1976. Though the record itself is now legendary, it could have been completely different if the band’s manager hadn’t stepped in with some timely advice.

Manager Chris O’Donnell came out to the farm where they’d been working up material and asked to hear what they’d come up with. They played him more than two dozen songs. At the end of the playback, he had notes and zeroed in on one particular track.

“It doesn’t sound finished, but there’s something I really like about this. I like the groove and where it’s going,” he told the band, as guitarist Scott Gorham recalls now. “How about you put that song in and take one of the songs on your original list out? We thought, ‘Well, let’s do that, because there’s at least one vote for the song.'”

It was a crucial vote for the song that became “The Boys are Back in Town,” a standout moment on the album and a classic in the Thin Lizzy catalog to this day. 1976 was a turbulent year for the Dublin rock group. While they released Jailbreak and the record began to build acclaim, their momentum would be derailed as Phil Lynott wound up in the hospital with hepatitis. The vocalist spent a stretch recuperating, but Thin Lizzy weren’t finished with the year yet. Thanks to an abundance of recordings and ideas, they eventually regrouped and released Johnny the Fox that same year.

Now, a new box set, appropriately titled 1976, collects both albums along with a wealth of additional material from the sessions, some fresh remixes to go alongside the original album mixes and a key live show recorded during the Jailbreak tour. Gorham recently joined Ultimate Classic Rock Nights host Matt Wardlaw to discuss the release and share his memories of the time period.

I enjoyed this new box set quite a lot. One of my favorite parts is the live show from the Cleveland Agora in 1976. It was a fun surprise to see that here.

That’s what I thought, too. You know, it was a pretty good show. It was a good representation of what we were back then. It was [leading up to] the Live and Dangerous era. I think that Cleveland show kind of let us know that we can put out a live album. And let’s seriously do the live album right instead of these one-off [performances], radio shows or what have you. The Agora show was kind of the preliminary [moment which led to] Live and Dangerous.

Listen to Thin Lizzy Perform ‘Jailbreak’ Live in Cleveland

Bands do a lot of things during a promotional cycle for an album. Did the experience of doing this show stick with you, or was it kind of a new thing, going back to it as you were working on this box set?

It was a bit of a new one and it was a nice surprise. Along with being able to put a new gloss on the older albums. We went in and did a different mix on each of the tracks for Jailbreak and Johnny the Fox, which I really enjoyed. I really had no intention of doing that, but Universal called me up and said, “Hey, we’ve got this producer, Richard Whitaker and he’s remixing,” blah blah blah — and I went, “Wait a minute, you’re doing what?” [Gorham takes on a surprised tone] So they said, “Yeah, why don’t you go over and have a listen, just to see what you think. I went over and met Richard and we got along great right off the bat.

The first thing he played me was the song “Jailbreak.” He’d found a lot of different tracks that we didn’t use on the actual original recording. He said, “Check out that cowbell here. You guys never used the cowbell on that.” I go, “You’re kidding, right?” I thought, “You know, that’s actually really cool.” I don’t know if it’s just because it’s a new thing that I hadn’t heard before. But I actually really liked it. There were other tracks we uncovered, different things that Phil had done vocally and different guitar riffs that weren’t added to the original album. Some of them got included because, yeah, you know, that actually fits and why didn’t we use that originally? I mean, did we take a vote? “Who wants this on here!” Okay, that riff didn’t get enough votes or something. I don’t know! We didn’t throw everything in just because it was new — but if it actually fit and sounded really cool, why not? Put it in there and let’s see what everybody thinks.

READ MORE: The Story of Thin Lizzy’s Biggest Hit, ‘Jailbreak’

What came back to you through the experience of revisiting these two albums for the box?

Well, one of the things is some of the tempos are really slow. Because you’ve got to remember, the first thing we’d do is we’d record the album and then, bang, you’re right out on the road. You immediately say, “Right, we’ve got to up the tempo on this. It’s a little bit draggy on the record.” So you’d up it a couple of beats. The other thing we did, I remember talking to Brian Downey, Thin Lizzy’s drummer. He was always disappointed with the drum sounds that he was getting. They really were completely different from what I was hearing and from what he was hearing on stage live. A lot of that, I’ve since found out, was the close miking that these engineers used to use back then. They didn’t really use the room, you know, the overheads and all of that. So there was no real breathing space in the drums. We didn’t touch anything that Brian played [with the updated remixes], but we put on a different sound for him and it really livened up the tracks. Instantly, it was like, “Damn, that’s more of the Brian that I remember,” you know, playing live with. It’s things like that which put a smile on my face when I go back and hear this new version.

The way the story goes, the band was kind of on the chopping block going into the Jailbreak album.

You’re absolutely right. You know, we were told by management, record company and even some fans, “Guys, you’ve got to come up with some magic here, or there’s the door. Don’t bother knocking trying to get back in, because it’s going to be over.” So that kind of put the fear of God in all of us a bit. This is going to sound really antiquated, but we bought ourselves a four track reel-to-reel recording machine and rented a big room at this farm outside of London. We spent three weeks out there, just demoing our asses off. We probably spent between eight and 12 hours a day just coming up with riffs — and Phil with his lyrics — different melody lines, guitar harmonies and all of that. At the end of the three weeks, we ended up with 25 songs and [then] you’ve got to come up with a list of 10 that you’re going to be able to put on the album. Interestingly, “The Boys are Back in Town” was not on that original list.

I’ll tell you why: Phil’s lyrics were great and there was a great bed of music to play on, but there were no harmony guitars on it at that point. So it was just this track, with none of the jangly bits. One of our managers, Chris O’Donnell, came down and said, “Well, let’s hear what you guys have recorded for the last three weeks. He sat through all 25 songs making notes and at the end of it, he said, “You know, this song here, ‘The Boy is Back,’ it doesn’t sound finished, but there’s something I really like about this. I like the groove and where it’s going. How about you put that song in and take one of the songs on your original list out?” We thought, “Well, let’s do that, because there’s at least one vote for the song.”

That’s where we actually started to work on [what became] “The Boys are Back in Town.” I finally came up with the riff. [Thin Lizzy guitarist] Brian Robertson immediately latched onto it and said, “Let me put a harmony to that.” As soon as he did that, those sections really lit up and it literally became the second hook of that song. So thank God the manager came down.

Listen to Thin Lizzy’s New Stereo Version of ‘The Boys are Back in Town’

How normal was it for the band to spend that amount of time demoing songs like that? Was there any one way that Thin Lizzy approached the album process, or did it change from record to record?

I think with Jailbreak and Johnny the Fox, being able to have our own tape machine and being able to get out of London and away from the chaos [was important]. It’s just you four guys in the room taping everything and every idea that came down. At the end of the day, you go, “Well, that song there, it sounds pretty good up until this point.” That other song idea and riff, let’s try putting that in the song there and gluing that at the end and see how it works. There was a lot of that which went down, like, gluing all of these different parts together, because we were never short on riffs, melody lines or anything like that. It’s just having the concentration to be able to sit down [with a certain number of band members], trying to glue all of the different parts together and having everybody satisfied with everything at the same time.

READ MORE: Weekend Songs: Thin Lizzy’s ‘Emerald’

That’s the eternal quest.

It’s a tough one. You know, the worst thing you want to have said — we always liked to think of ourselves as this ultra original band, we didn’t want to sound like anybody else, ever. Forget about it. So the worst thing anybody could say when you brought in a new part or a new song was, “That reminds me of this other song.” Now, you’re in a corner and you have to defend yourself. “I’ve never heard of that song before,” so you really had to go into defense mode.

One thing that’s always been a bit murky about Johnny the Fox, is the participation of Phil Collins. How did you guys know him?

I think Phil [Lynott] knew him. He was just one of those really cool guys and a good, good drummer and percussionist. He was in town, so we just asked him, “Hey, Phil, can you come down and put some percussion on this song or that track?” He said, “Yeah, absolutely. No problem!” He came straight down and did it.

Those kinds of things never seemed to be a problem. If someone called me up, I’d go, “Yeah, sure. come down!” There was a lot of interplay going on with a lot of different bands at the time. It was because we were all friends. Everybody knew that we were up against it. There’s a war going on out there and we’re all in this together. That kind of thing, you know? So it was all pretty friendly stuff.

Yeah, and Phil Collins was always one of those guys that whether it was Brand X or whatever, he just loved to play. That came through when you see the various guest appearances he made on people’s albums and songs. Ian McLagan was the same way.

You hit the nail right on the head there. These are guys who just love to play. They’re people who love to be put in a different situation. I’m great with this bunch of guys here that I’m used to. What happens if I get thrown in with this bunch of guys over here? I did a session with David Cassidy one day, for God’s sake. I don’t really consider myself a session guy, but that was so odd, because he was such a pop guy. He had his own TV show and all of that. I thought, “This is kind of a weird one, I’m going to go down there and do that.” He turned out to be an okay guy and the track was pretty cool. I did it and that was it, right? But those are the kinds of things you like to do, to test yourself every once in a while to see what your chops are really like as a person and a musician.

When it comes to this new box set, was there someone in the band who was an archivist type? Some bands saved all of the tapes and others didn’t.

That’s a really good question. You know, a lot of the multi-tracks [tapes] wherever we recorded, kind of stayed in that studio, right? We felt pretty good about leaving them there, because they’re nice and safe. They all had their own little lockup. But there was a a studio here in London that their lockup just got so full of multi-tracks. they started to throw them out into the trash cans in the back of the studio. I don’t know how this guy did it, but maybe he was there at the studio at the time. He saw these boxes in the trash can and he was going, “Oh, my God, they’re just throwing this stuff out.” He grabbed [the tapes] and threw them in his car. There must have been eight or nine boxes of multi-tracks tapes. He kept them for a long time. Then, he finally admitted that he had him, but he wanted to get paid for it. We paid him for it. Because, you know, I thank God he did it. Thank God he had moxie enough to go to that trash and pick them out and save these multi-tracks, right? So, you know, we would have to actually have these later on in life. I didn’t mind paying them at all.

Thin Lizzy Albums Ranked

Phil Lynott carved out a lofty reputation as not only one of his generation’s greatest natural rock stars, but as a songwriter’s songwriter.

Gallery Credit: Eduardo Rivadavia