Without a solid rhythm section, there’s little hope for a rock band.

Harsh as that may seem, it really cannot be overstated the importance of the cohesion between a drummer and a bassist — they serve as the foundation of a band’s sound, and without their cooperation, both with the other instruments and with one another, there is no anchor for the music to hold onto.

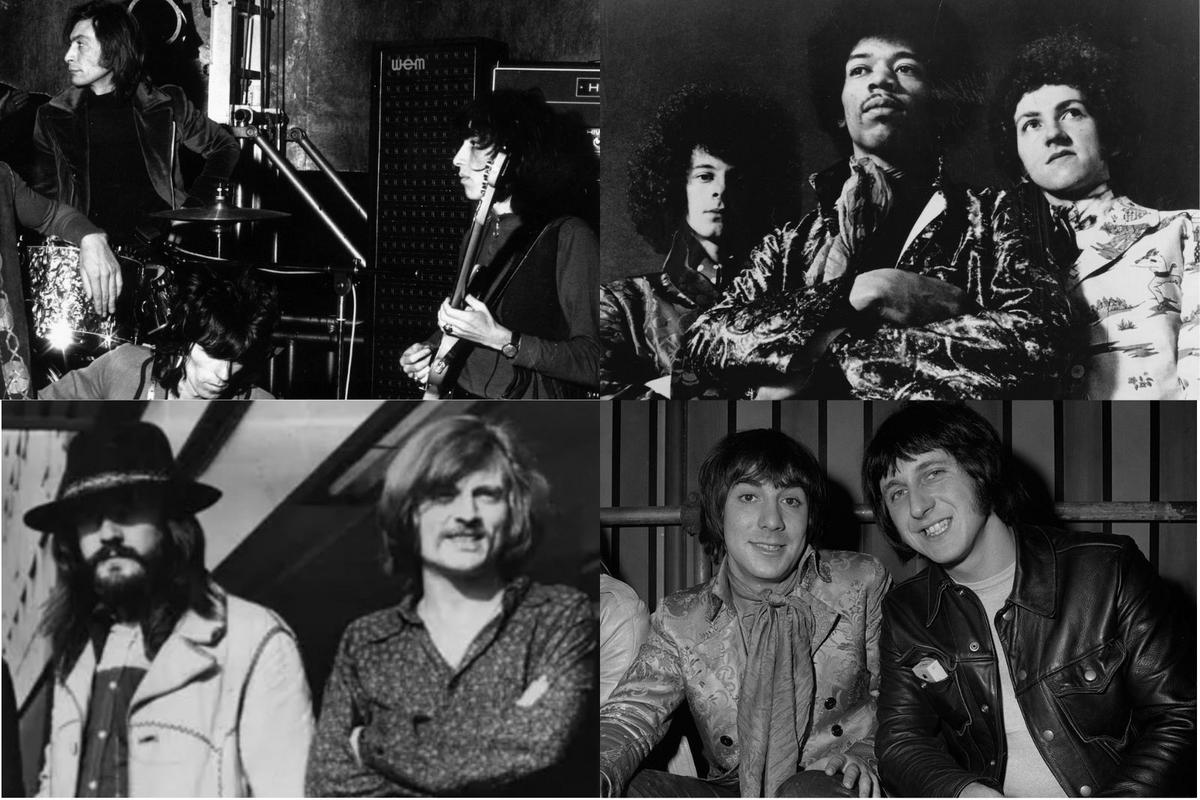

Sure, lots of fans like to watch the lead singer prance across stage, or the lead guitarist shredding up a solo — and those things are undoubtedly part of the rock ‘n’ roll group experience — but the real meat of a rock song comes from the rhythm section. Below, we’re taking a look at the “Big 4” of rock rhythm sections — pairs of people without whom their respective bands may very well have flopped.

John Bonham and John Paul Jones

Evening Standard, Getty Images

Bassist John Paul Jones knew instantly that he and drummer John Bonham were a perfect fit, even as young men at 22 and 20 years old, respectively. “When you’re young and come up through the bands you know immediately, well he’s not up to much or my God, I can’t work with this [bloke],” Jones once said in an interview with Bonham’s brother, Mick. “With Bonzo and I, we just listened to each other rather than look at each other and we knew immediately because we were so solid. From the first count in we were absolutely together.”

Of course, one of the defining features of Led Zeppelin was their utterly enormous sound — certainly not what you’d expect from a group of just four people. Particularly at the time Led Zeppelin formed in the late ’60s, few rock bands were gravitating toward the heavier sound they were, which necessitated a robust rhythm section so that Jimmy Page‘s solos and Robert Plant‘s wailing vocal had something to land on top of. “I don’t really like rock drummers because they’re all a [bit] ‘tippy tappy’ with nothing really ‘booty’ underneath,” Jones continued, “and no real understanding of what James Brown called ‘The One.’ Bonzo did.”

Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding

Redferns, Getty Images

One lead guitarist does not a proper rock band make, even if that lead guitarist is Jimi Hendrix. Enter bassist Noel Redding and drummer Mitch Mitchell, who linked up with Hendrix within approximately a month of each other in1966.

Two things set Redding and Mitchell apart from other rhythm sections. For one thing, Mitchell’s chief influences were jazz drummers, leading him to develop a more refined style different from other American rock drummers. Additionally, Redding had first been a professional guitarist up until switching to bass for the Jimi Hendrix Experience, meaning he was quite familiar with the tendencies of an electric guitarist like his band’s frontman. “Noel is an adequate, a very competent guitarist,” Mitchell said in a 1971 interview with Sounds, “and with his knowledge of the finger-board of the guitar he has the chance of being a superb bass player, barring very few.”

It helped that Hendrix trusted Redding to hold the fort down no matter how wild his own playing got. “We were a very spontaneous group – just plug in and play. Except for the occasional riff Jimi would ask me to double, I was free to come up with my own bass lines,” Redding explained to Bass Player in 1993. “For the most part, I would anchor the tune while Jimi and Mitch Mitchell went off on tangents. Playing chords helped to fill out the sound while he was soloing, but no matter how far away they went, they knew I’d be there when they got back. I went off on a few tangents myself, but overall I preferred to keep it simple. I think that’s the job of any good bass player.”

Keith Moon and John Entwistle

Keith Moon and John Entwistle

Keith Moon of the Who was not the sort of drummer that most musicians would find easy to play with. Like his personality, his drumming could be unpredictable and unruly, even if wonderfully powerful. Yet, John Entwistle seemed to have an innate talent for keeping Moon — and sometimes the whole band — on track.

“Keith didn’t particularly keep time too well,” Entwistle once said to DRUM! magazine. “If he was feeling down the songs would be slow, if he was feeling up the songs would be too fast, and if he felt normal the songs would be normal. I would get very frustrated because he couldn’t actually play hi-hat at all, just a mess of cymbals. I knew he was a one-off [one of a kind] drummer, but in the same way as the rest of us were one-off. We constructed our music to fit ’round each other. It was something very peculiar that none of us played the same way as other people, but somehow, our styles fitted together.”

And while Moon provided the sheer power, Entwistle offered the details. “John’s bass sound was like a Messiaen organ,” guitarist Pete Townshend said to Rolling Stone in 2019. “Every note, every harmonic in the sky. When he passed away and I did the first few shows without him, with Pino [Palladino] on bass, he was playing without all that stuff. … I said, ‘Wow, I have a job.'”

Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman

William Lovelace, Express, Getty Images

When one thinks of the Rolling Stones, words like “debauchery” perhaps come to mind. But for however grandiose Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were, drummer Charlie Watts and bassist Bill Wyman were more or less the opposite — quieter, more in the background and yet equally as important to the success of the band. “I liked him straightaway,” Wyman told The Guardian in 2001. “I was closer to him than any of the others, but then we were the rhythm section. We’re totally different personalities, but we were the only ones who were always on time, so we were always chatting away to each other. “

It worked a little bit like this: Watts tended to follow Richards’ lead, carefully listening to him and utilizing his own jazz sensibility. Wyman followed Watts and the result was a perfectly intertwined rhythm section and rhythm guitarist — more of a rock ‘n’ roll rarity than you might think.

“In 30 years of the Stones, I never fell out with Bill,” Watts added to The Guardian. “He’s a very kind person, easy-going. We were very close in the band structure. We were the rhythm section, so his problems were nearly always my problems. When he left the band — God, bloody hell! — I could have killed him. We had two weeks where I was playing three hours a day to audition new bass players. I was dead at the end, my bloody hands were killing me.”

Famous Final (or Not-So-Final) Concerts

Final concerts aren’t always announced beforehand. Sometimes, they’re not even final at all.

Gallery Credit: Nick DeRiso